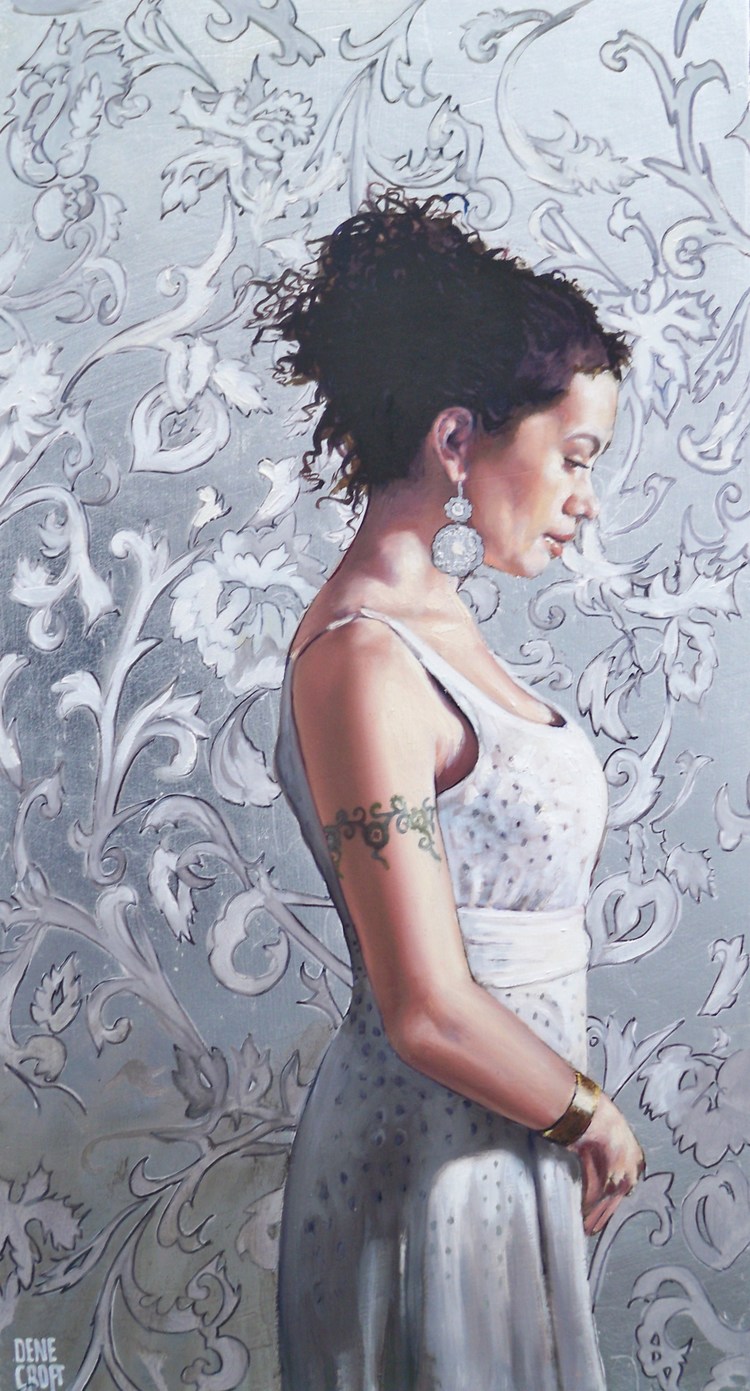

A few essential steps in building a fabulous portrait in oil . . .

As with any artistic endeavour, the success or failure of a project is a result of being the sum of it’s parts . . . the thoroughness and accuracy of the attention to those “parts” plays a huge role in ensuring a successful outcome . . . that being said, the first and most important “part” is working with the model. While working with your model, experiment with direct and indirect lighting, reflected light and creating mood and ambience with shadows. Consider the story that you are trying to tell – pose, gesture, expression and lighting all play very important parts in that, so your model will need direction – most are far more comfortable with clear instruction and direction than not. Most of the shots that I use for my paintings are taken ‘between’ poses while the model is unaware and consequently, more relaxed. At all cost, resist using old snapshots or candid images of family and friends – these were never taken to make good paintings – and rarely do. Allow yourself to paint using reference material that closely mimics working with a live model. A photo taken with a good camera printed on an 8×10 glossy could be considered a minimum in terms of reference standard – things will get tricky enough during the painting process, so give yourself every available advantage . . .

You are looking to create interest and drama where, perhaps there isn’t much . . . irregular and odd canvas sizes can help achieve this. Strong directional lights will cast long shadows and create a chiaroscuro (dark/light) effect. Think about quiet spaces and how the negative spaces create added drama and interest to the composition. Think about contrasting shapes, colour and textures. Keep the elements in your composition simple – less is very often more and coupled with some clever use of negative space, will go a long way towards creating a more contemporary look and will add that interest and drama that you are looking for – remember that the spaces around the subject can very often contribute as much or more to the success of the finished painting.

Build your canvas . . .

If you haven’t built your own canvases before, you need to give this a try – NEVER attempt to squeeze your subject into the format of the canvas that you happen to have at hand – rather, build your canvas around your formatted composition – the ‘square peg into a round hole” approach never works. Stretcher bars and canvas ( use at least 10 oz) can be picked up from your art supply store. Buy yourself an inexpensive staple gun, a pot of gesso and a piece of sand paper – takes about half an hour and costs slightly less than a pre-stretched canvas – the superior quality is an added bonus.

Prepare your palette . . .

Decide what you might be able to accomplish in the time that you have for the current painting session and set your palette up based on that focus. Having your colours mixed and ready to go will save you time and eliminate guess work. It is often tempting to try to create your colour for the job at hand by mixing from whatever you happen to have left on the palette – doing so means you’ve stopped caring. Take a break at this point, clean your brushes and reset your palette. Guess work will take you down a dark and murky road. . .

Under paint, edges etc . . .

Those of you that know me know that I place a lot of emphasis on preparation, careful drawing and under paint. The drawing of the composition to the canvas is really important. Whether you draw with a brush, charcoal or pencil is unimportant, but make a few pre-studies and work out your issues in the drawing before you commence painting. I use the grisaille technique as an underpaint however a toned canvas works equally well – try using a neutral colour such as raw umber.

Mind those edges! . . . there are two types of edges – soft and hard. The use of both will create interest , mood and depth of field. The human eye is able to see objects peripherally – objects appear blurred and unfocused – soft edges. Soft edges apply to objects that are in the background and further away from the eye. Use your soft and hard edges to guide the viewer through your painting.

Brushes and paint . . .

Much can be discussed re the virtues of the endless choices that we have today. I’m only going to talk of my own experience. Buy the best paint that you can afford; that being said, many – if not most of my paintings have been painted with what might be considered, middle-of-the-road paint. I mainly use Stevenson paint. Though I am an oil painter, I use only acrylic brushes. I very often find oil brushes too stiff for my work – your choice of brushes will very much be determined by your painting style. I use between 6 and 8 colours – 3 primaries and 5 “convenience” colours. I use tear off, paper palettes. I use a combination of linseed oil and mineral spirits as a medium. I use OMS as a clean-up medium. I prefer 10 oz canvas to board, I prefer pencil over charcoal and I am not fond of projectors or technology based assists – I generally keep things very simple and uncomplicated.

The dance . . .

. . . remember, it’s all about value and colour. Prepare your value study before you jump into colour. Stand back and consider your work often. Keep your eye on the ball – Singer-Sargent used to say that he spent 70% of his eye on the subject and 30% on the paint – I definitely agree with this approach. Meaure and re-measure, accessing and adjusting one element against another. Paint from the distance that your finished work will be viewed at. Paint using adequate lighting similar to the light under which your work will be typically displayed. Try to get into the habit of holding your brush as far down the handle as possible – painting with your nose pressed up against the canvas and a vice grip on the ferrule is a very bad habit that most new painters adopt from the outset and often have a great deal of difficulty letting go of. This type of approach to technique leads to preciousness – not at all helpful in achieving a casual “painterly” style and leads to over control and an inability to make all the necessary assessments and adjustments that you need to be constantly mindful of – stand back and give yourself lots of room. NEVER dismiss flash ideas and intuitive responses. My experience has taught me that these moments between you and your work can generally be relied upon and often lead to some surprising result.

Remember that this process of painting is a dance . . .